The Psychological Stress Model – A First Principles Guide to Mastering Your Stress

Grounded in the Biopsychosocial Model, this note explores one of the core mechanisms behind our stress responses. Before diving in, make sure you grasp the foundational Definition of Stress.

Stress is often misunderstood—not merely a nuisance or a “bad thing,” but an adaptive system shaped over millennia. In the past, a human fleeing from a lion would experience a surge of stress that helped them survive. However, in today’s world, we face complex, persistent, and frequently self-created stressors, and we are much less likely to encounter life-or-death situations.

Yet to truly master stress—rather than just survive it—we need to strip away the confusion and see what’s really happening under the hood. Once we know how the system works, we can use it to our advantage—turning an ancient survival mechanism into a catalyst for personal growth.

1. Deconstructing Stress from First Principles

Let’s start with a quick thought experiment. Imagine you’re preparing for a big presentation at work—lights are set up, your colleagues are watching, and you feel a knot in your stomach. No lion is chasing you, but the nervous energy is eerily similar. Your palms sweat, your heart races. Why?

Because the body has one fundamental response system for any perceived threat: stress. That’s why a text from your boss or a looming public speech can trigger many of the same reactions as a genuine physical danger.

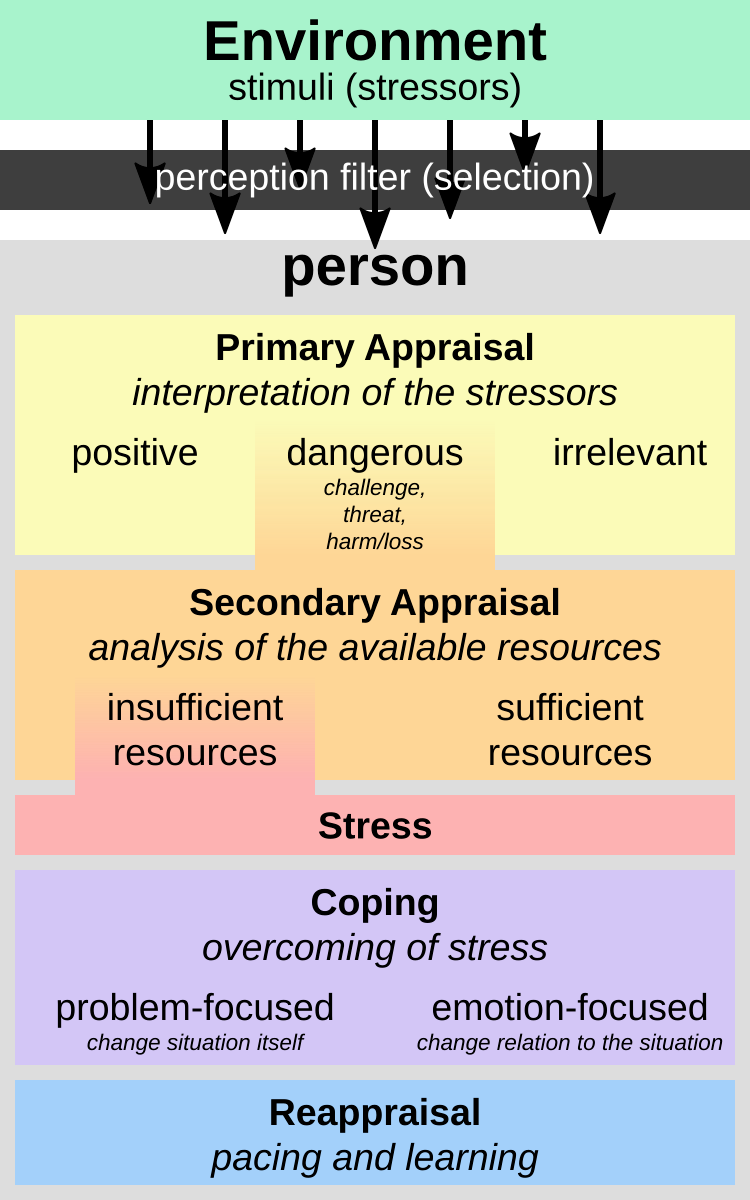

2. Interactions Within the Stress Response System

Stress isn’t just “thing happens, you freak out, the end.” It’s a dynamic web of feedback loops, shaped by both the world around you (external factors) and what’s going on inside your head (internal factors).

Internal vs. External Inputs

- External Inputs: Real-world events you can see or measure, like deadlines, traffic jams, or difficult conversations.

- Internal Inputs: Personal beliefs, thought patterns, past experiences, and attitudes—like perfectionism, self-doubt, or a growth mindset.

The Four Steps of Stress

-

The Stressor

Any situation (external) or thought (internal) perceived as demanding or threatening.- Physical: Extreme temperatures, pain.

- Social: Uncomfortable interactions, performance reviews.

- Cognitive: Overthinking, catastrophizing, fear of the unknown.

Example: Two people face the same looming deadline, but one shrugs it off while the other loses sleep. The difference? How each one interprets the stressor.

-

Primary Appraisal

You make a snap judgment:- “Is this irrelevant, or could it be a threat?”

If you label it threatening, the process continues.

Example: Imagine Sam, who has a big presentation next week. Sam immediately thinks, “If I mess this up, everyone will laugh.” Primary appraisal says: “Danger!” Another speaker might see the same event as an exciting challenge.

- “Is this irrelevant, or could it be a threat?”

-

Secondary Appraisal

If it’s threatening, you next ask:- “Do I have the skills or resources to handle this?”

- “If not, can I acquire them?”

Example: Sam asks himself, “Have I practiced enough? Do I have slides ready? Could I ask a colleague for feedback?” If Sam believes he can prepare, stress decreases. If not, anxiety skyrockets.

-

The Stress Response

Now your body and mind gear up for action:- Physiological: Heart pounding, cortisol surge, muscles tensing.

- Emotional: Feeling anxious, uneasy, or maybe fiercely determined.

- Behavioral: Fight (face the challenge), Flight (avoid it), or Freeze (paralysis).

Example: Sam either doubles down and rehearses (fight), tries to avoid presenting (“Maybe I’ll call in sick...”), or sits there, unable to practice effectively (freeze).

Coping Mechanisms

When faced with a threat, you engage in coping: the cognitive and behavioral moves you make to reduce the sense of danger and restore balance. This leads us straight into our next section.

Real-World Scenario: A Short Story

Let’s watch the entire process in action. Suppose Sam learns he must present to a big client in just two days.

- The Stressor: Last-minute presentation.

- Primary Appraisal: Sam thinks, “This could be disastrous.”

- Secondary Appraisal: Sam checks his resources: “I’ve got one night to prepare, a friend who can help me rehearse, and decent speaking skills, but I’m still nervous.”

- Stress Response: His heart races. He considers avoiding it altogether but decides to fight the anxiety.

Next, Sam notices stress amplifiers in himself: a perfectionist streak that demands he do it flawlessly, plus impatience that flares up when things don’t go smoothly. At the same time, he sees he can adopt a stress-is-enhancing outlook. “A bit of adrenaline can actually help me focus,” he tells himself. This reframing switches Sam’s perspective from “I’m doomed” to “This might be a chance to grow.”

3. Coping: The Levers We Can Pull

Stress is intricate, but that also means there are many points for intervention.

-

Instrumental (Problem-Focused) Coping

Tackle the stressor directly.Example with Sam: He seeks a colleague’s help to practice the presentation, clarifies the client’s requirements, and updates his slides. He’s dealing with the problem at its root.

-

Emotional (Response-Focused) Coping

Manage how you feel about the stress.Example with Sam: He reframes negative thoughts (“They’ll laugh at me!”) into something more helpful (“This is a chance to show them what I know”). He also takes short breaks to clear his head if anxiety spikes.

-

Regenerative (Energy-Restoring) Coping

Replenish your mental and physical reserves.Example with Sam: After a long practice session, he goes for a jog or listens to music to decompress. This helps reduce tension and refuel his energy for the next day.

No single method works for everyone every time. True mastery comes from experimenting with all three forms of coping, then choosing the ones that best fit the situation.

4. From Theory to Action: Designing an Effective Stress Strategy

Mastering stress isn’t one-and-done; it’s iterative:

-

Identify Your Stressors

- Keep a Stress Journal or use something like The Disposition Model to track what sets you off.

- Some stressors are best removed altogether—if possible.

-

Analyze Your Appraisals

- Are you blowing a small issue out of proportion?

- Could you see a big challenge as an opportunity to grow?

-

Test Different Coping Strategies

- Experiment with problem-focused, emotional, and regenerative techniques.

- Maintain a short list of go-to tools so you’re never at a loss when stress hits.

-

Measure Outcomes

- Which methods worked? Double down.

- Which didn’t? Adjust or drop them.

- Keep refining, just as Sam did before his presentation.

Final Thoughts: Stress as a Tool

Stress isn’t the villain it’s often made out to be. It’s a universal response system that can either sweep us away or propel us to new heights. By mapping out the process (Stressors → Appraisals → Responses → Coping) and spotting where your mindset or beliefs might amplify fear, you gain real control over what happens next.

Use these principles as building blocks. Experiment and refine. In doing so, you’ll transform stress from something that holds you back into something that pushes you forward.